WRITING

The Indignities of Daily Life (Excerpt)

Lecture, Mason Gross School of Art

Rutgers University

2006

The Indignities of Daily Life (Excerpt)

Lecture, Mason Gross School of Art

Rutgers University

2006

Born in Macclesfield, Scotland in 1968, David Shrigley studied at the Glasgow School of Art and has lived in Glasgow since. He cites “'found' artwork; graffiti, shopping lists, telephone doodles, hand-drawn maps and diagrams” as graphic influences; “I also like outsider art but I think my real interest lies in that which is 'accidental' rather than untutored. In terms of his content and style, he recognizes American author Donald Barthelme as a dominant influence: “What I really like about his writing is the way that he allows you glimpses of great profundity in amongst the playful 'literary exercises' he seems to be engaged in.”

Shrigley self-published his first two books of drawings, but they exhibited a “cartoon-like” stylistic departure from his original work and failed to resonate with those familiar with his sketchbooks: “I was of course a failure at being a cartoonist. . . In 1994 I published my third book Blanket of Filth. The drawings in this book were taken directly from my notebook without any attempt to make them look nice.” Acknowledging an affinity for aesthetically crude drawings, he maintains that they nonetheless have to “communicate ideas.”

Shrigley does not consider himself a cartoonist, but perhaps his opinion of cartooning is low. In his 1998 Introduction to Why We Got the Sack from the Museum Will Self writes,

The very best cartoonists achieve both reductio ad absurdem — ideas and captions internally undermining one another; and a reductio ad infinitum — captions and ideas reflecting each other in an endless hall of reflexivity. . .[they come] closer to ideogrammatic forms of written language, such as Chinese characters. . .[I]n some bizarre future one could imagine a vast keyboard and on each key a Shrigley image, all ready for one to type out Shrigleyish.

Shrigley plays within a world that, in aesthetic terms, only coarsely references the actual. His art is a game in which he pits his wit against death and indignity, rendering both on a small scale. Bracewell writes, “[His] drawings exist in the singular world of their own sealed vision.” In "David Shrigley, a Vandal and a Moralist or: The Ten Fingers of Your Left Hand", Frédéric Paul, writes, “Bringing language to a point nearing dislocation, he is without equal in making absurd associations, in speaking trivially about important subjects, cruelly about sensitive subjects, and seriously about perfectly irrelevant subjects.” Shrigley denies any initial agenda - “I start with nothing in my head. I sit at my desk and draw for 8 hours a day” - but concedes, “[o]bviously the absurd is an important part of what I do. . .” His art lies as much in his editorial process as it does in the act of drawing:

I have a box that I put drawings into when they're finished. It is called my 'artistic distance' box. I leave the drawings in the box for weeks or months (sometimes years) and then I have a look at them again. If they're still no good after 2 years I throw them away. If they're no good in the first place I don't even put them in the box, they go straight in the bin. I think I throw a lot more away now than I used to. Last month I threw away 200 drawings. It's a good thing to do once in a while but it can be dangerous as it's quite addictive and you can end up throwing all of your possessions away; furniture, CDs, legal documents, or worse still you can start throwing away things that don't belong to you such as your girlfriend's clothing or rare books that have been lent to you.

"I say to myself – sometimes, Clov, you must learn to suffer better than that

if you want them to weary of punishing you – one day." -Samuel Beckett, Endgame

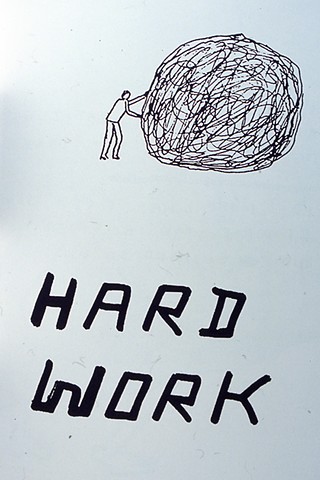

In terms of process, David Shrigley exhibits a Cageian openness. In 2003, he told Neil Mulholland: “All my work is pretty intuitive. . .I have starting points, but I have no idea where I'm going.” Shrigley also incorporates futility. He depicts situations in which characters succumb to non-lethal forces, or battle with the petty or ludicrous. With absurdity as his weapon, Shrigley establishes his commentary within an idiom of fictive characters and circumstances that speak to real frustrations and dilemmas. His drawings protest the indignities of daily life, exaggerating actions as they emphasize their impact. They provide relief from the tyranny of petty everyday affronts even as they depict an ultimate succumbing to those very offenses.

Michael Bracewell writes, “Shrigley’s drawings. . .are concerned with the unreported tragedies of everyday life.” Shrigley reinforces tragedy as he diffuses it. There is a cynicism to his form of play. He toys with doom, employing an endgame of sorts. David Ross writes:

When Samuel Beckett wrote Endgame, his dark tragic comedy in one act, he was clearly setting out a bleak dead-world in which the notion of art or any hint of it was seen as a particularly cruel joke. Here indeed was an endgame filled with desperate moves made in full consciousness of their futility, yet bound to their efforts by the rules of the game itself.

Shrigley’s irreverent humor is reminiscent of school days when scrawling on the inside of a notebook constituted a rebellious act. Yet he does so from the present, as an adult and though his voice carries a rebellious chord, it incorporates resignation, an acknowledgement of present and past realities, of inevitable barriers. Bracewell writes, “The humour in his work conceals a vision of humanity, which is derived from religious allegory and the deep absurdities which accompany notions of moral edification or social conditioning.” Shrigley treats the page as an interface where his intelligence battles tedious, potentially soul-numbing day-to-day experiences. It is an interface he returns to with each drawing.

Shrigley self-published his first two books of drawings, but they exhibited a “cartoon-like” stylistic departure from his original work and failed to resonate with those familiar with his sketchbooks: “I was of course a failure at being a cartoonist. . . In 1994 I published my third book Blanket of Filth. The drawings in this book were taken directly from my notebook without any attempt to make them look nice.” Acknowledging an affinity for aesthetically crude drawings, he maintains that they nonetheless have to “communicate ideas.”

Shrigley does not consider himself a cartoonist, but perhaps his opinion of cartooning is low. In his 1998 Introduction to Why We Got the Sack from the Museum Will Self writes,

The very best cartoonists achieve both reductio ad absurdem — ideas and captions internally undermining one another; and a reductio ad infinitum — captions and ideas reflecting each other in an endless hall of reflexivity. . .[they come] closer to ideogrammatic forms of written language, such as Chinese characters. . .[I]n some bizarre future one could imagine a vast keyboard and on each key a Shrigley image, all ready for one to type out Shrigleyish.

Shrigley plays within a world that, in aesthetic terms, only coarsely references the actual. His art is a game in which he pits his wit against death and indignity, rendering both on a small scale. Bracewell writes, “[His] drawings exist in the singular world of their own sealed vision.” In "David Shrigley, a Vandal and a Moralist or: The Ten Fingers of Your Left Hand", Frédéric Paul, writes, “Bringing language to a point nearing dislocation, he is without equal in making absurd associations, in speaking trivially about important subjects, cruelly about sensitive subjects, and seriously about perfectly irrelevant subjects.” Shrigley denies any initial agenda - “I start with nothing in my head. I sit at my desk and draw for 8 hours a day” - but concedes, “[o]bviously the absurd is an important part of what I do. . .” His art lies as much in his editorial process as it does in the act of drawing:

I have a box that I put drawings into when they're finished. It is called my 'artistic distance' box. I leave the drawings in the box for weeks or months (sometimes years) and then I have a look at them again. If they're still no good after 2 years I throw them away. If they're no good in the first place I don't even put them in the box, they go straight in the bin. I think I throw a lot more away now than I used to. Last month I threw away 200 drawings. It's a good thing to do once in a while but it can be dangerous as it's quite addictive and you can end up throwing all of your possessions away; furniture, CDs, legal documents, or worse still you can start throwing away things that don't belong to you such as your girlfriend's clothing or rare books that have been lent to you.

"I say to myself – sometimes, Clov, you must learn to suffer better than that

if you want them to weary of punishing you – one day." -Samuel Beckett, Endgame

In terms of process, David Shrigley exhibits a Cageian openness. In 2003, he told Neil Mulholland: “All my work is pretty intuitive. . .I have starting points, but I have no idea where I'm going.” Shrigley also incorporates futility. He depicts situations in which characters succumb to non-lethal forces, or battle with the petty or ludicrous. With absurdity as his weapon, Shrigley establishes his commentary within an idiom of fictive characters and circumstances that speak to real frustrations and dilemmas. His drawings protest the indignities of daily life, exaggerating actions as they emphasize their impact. They provide relief from the tyranny of petty everyday affronts even as they depict an ultimate succumbing to those very offenses.

Michael Bracewell writes, “Shrigley’s drawings. . .are concerned with the unreported tragedies of everyday life.” Shrigley reinforces tragedy as he diffuses it. There is a cynicism to his form of play. He toys with doom, employing an endgame of sorts. David Ross writes:

When Samuel Beckett wrote Endgame, his dark tragic comedy in one act, he was clearly setting out a bleak dead-world in which the notion of art or any hint of it was seen as a particularly cruel joke. Here indeed was an endgame filled with desperate moves made in full consciousness of their futility, yet bound to their efforts by the rules of the game itself.

Shrigley’s irreverent humor is reminiscent of school days when scrawling on the inside of a notebook constituted a rebellious act. Yet he does so from the present, as an adult and though his voice carries a rebellious chord, it incorporates resignation, an acknowledgement of present and past realities, of inevitable barriers. Bracewell writes, “The humour in his work conceals a vision of humanity, which is derived from religious allegory and the deep absurdities which accompany notions of moral edification or social conditioning.” Shrigley treats the page as an interface where his intelligence battles tedious, potentially soul-numbing day-to-day experiences. It is an interface he returns to with each drawing.